Most schools host some version of a science fair, a months-long project in which students dive deep into a topic of their choice and show off their work on a presentation day. Science fairs build independence (as long as a parent doesn’t hijack the project), foster intrinsic motivation because the student chooses the topic, and let students actually practice the scientific method. When student choose their research topic wisely, meaning it’s something they are actually interested in, they are more willing to invest effort, which is critical for ADHD types. Because the work spans weeks or months, students must practice time management, set priorities, and decide how to meet deadlines. Visual aids must be clear and well-organized, research should be thorough, and the final presentation should be confident and well-prepared. In short, science fairs create a powerful, authentic learning environment.

Science Fairs teach students the scientific method: asking a question, forming a hypothesis, gathering materials, following a procedure, identifying variables, recording results, and drawing conclusions. These steps guide students to think like scientists, grounding their learning in inquiry and experimentation. Recognizing that the scientific method can be applied across various domains, science fairs can also inspire projects in engineering, technology, and other fields, expanding the scope of student inquiry and engagement.

At my school, we’ve also embraced something I wish more schools would adopt: an Inventors Fair we call Design for Good. Like the Science Fair, it is built on a process—this time, the Engineering Design Process. Students define a problem, identify constraints, research, imagine multiple solutions, plan their approach, build prototypes, test and evaluate, improve, and finally communicate their invention. Even if your school doesn’t host an Inventors Fair (yet!), I'm sure you investigate inventions in your regular classroom curriculum. Whether you are exploring the fundamental needs of humans, historical inventions that changed the world, or more modern scientific advancements, inventions naturally pop up all over.

The engineering process shares plenty of similarities with the scientific method, but it offers its own unique perspective. Students really get to harness their creativity without the constraints of an experimental model. Failure is not a bad thing in the engineering process, but a step in the right direction toward prototype development. In a Science Fair, when the result doesn't match our hypothesis, even though this information could be very worthwhile, the scientist often feels disappointed. It feels like a lot of work was wasted for an unintended result. This is not the case in the Engineering Process, where someone's work isn't done after one result; instead, that result informs the changes needed for the version. Here, we see students use problem-solving skills repeatedly.

So, how do we integrate our PE curriculum with invention? The students invent their own sport! The Invent a Sport Lesson Series takes weeks, but it allows the students to apply their engineering process skills in a collaborative environment. Usually, at an Inventor's Fair, each student makes their own project, so they have complete say in how they develop their invention. To invent a sport, you need collaboration. You have no choice. This collaborative process, full of arguing, debating, ideating, and so on, is not just reinforcing the engineering process but also working on a whole set of SEL skills. Can the students use empathy to understand what the other group wants and meet them halfway? It's a challenge, but a crucial life skill that everyone needs to practice.

To follow the engineering process, the first step is to define the problem, but in this case, we know we are making a sport, so we have to define "What is sport?" instead. This is a Socratic discussion on what sport is. I ask a student to define a component of sport, repeat their answer to the group, and ask everyone to try to think of an example of a sport that doesn't fit the definition provided by the original student. In this way, we naturally discover different types of sports, such as physical activity sports, coordination sports, and motor sports. Since this is a PE class, the sport we are going to invent will require physical activity, but it's always a lively discussion on what constitutes a sport and what does not. In recent years, the most hotly debated question has been whether Esports count as a sport. This year was no different, with the gamers saying it absolutely was and non-gamers arguing against it. What is your opinion?

The reward for taking a chunk of PE time to talk about sport is that the kids get to play their most-requested favorite game, dodgeball. However, this is not ordinary dodgeball. After agreeing on a few basic ground rules, we manipulate the playing environment after every game. We do so because we are looking at the next step in the engineering process: defining constraints. Where a player is allowed to go, or the constraint of the playing area, can dramatically alter the feeling of the same game. Some skills are leveraged more than others based on the playing area, strategies change, yet the core rules still apply to every version. With a slight twist at the end, the students realize that constraints are an essential component of invention. Without constraints, you have everything, which is kind of the same as saying you have nothing. The constraints of a game shape the game's objective, focus, and strategy. Even if you don't go through with the whole 'inventing a sport from scratch,' this first lesson is a crowd pleaser and gets them thinking critically about the power of constraints, since they will viscerally experience the difference. It's interesting to see that every student has a favorite version, but it's not always the same across the board. This also reflects real life: not everyone likes the same sport, and it's one of the reasons we have such a variety of sports to play and compete in.

Here is the lesson plan for the first week of the Invent a Sport Lesson Series. Even if you don’t intend to go through the whole process, you can use this lesson as a one-off that the students will absolutely love!

· After defining "sport," it's time to play dodgeball! But we are going to play many mini-games of dodgeball as we explore the first part of the engineering process: constraints. How we constrain the playing area will dramatically change our perception of the game, even when we keep the basic rules the same through each game.

· The first version we will play will be the simplest, and the rules we introduce for this game will carry over from game to game. Only the playing area will change. Split the class evenly, taking into account things like throwing power, catching ability, etc.

· Here are the core rules we will use for our dodgeball games:

o Both teams start at their endline to begin the game. There will be dodgeballs on the center line to retrieve once the game begins.

o The center line is a boundary that a player cannot cross or step over. They are allowed to reach over to retrieve a ball as long as their feet remain on their side. Stepping over the line is an “out.”

o The game begins with both teams running to the center line and batting the dodgeballs back to their teams. Players are not allowed to immediately pick them up and throw.

o If a player is hit with a dodgeball, they must sit down where they were hit.

o Catching a dodgeball gets the thrower out if they can identify who threw it.

o If a seated player catches a dodgeball, they may stand and play again.

o If a player is holding a dodgeball, they can use it like a shield to deflect. However, a player cannot catch a ball while holding a ball.

§ Some players try to get around this by quickly dropping the ball in their hand to catch the oncoming throw, but this requires a lot of skill.

o After 1 to 2 minutes, the game ends, and the team with more standing players wins the round.

· For the second round of the game, we shrink the playing area to the basketball court. This means the students should start at their baseline for basketball. While this is not a dramatic change, stepping outside the basketball boundary lines is an out.

o This rule catches players who typically stand as far away from the midline as possible, and players who are retrieving dodgeballs that have left the basketball court.

· The third round of the game uses volleyball's boundary lines. Players will have to be more careful when throwing, as it is very easy for a ball to roll out of bounds and be unretrievable.

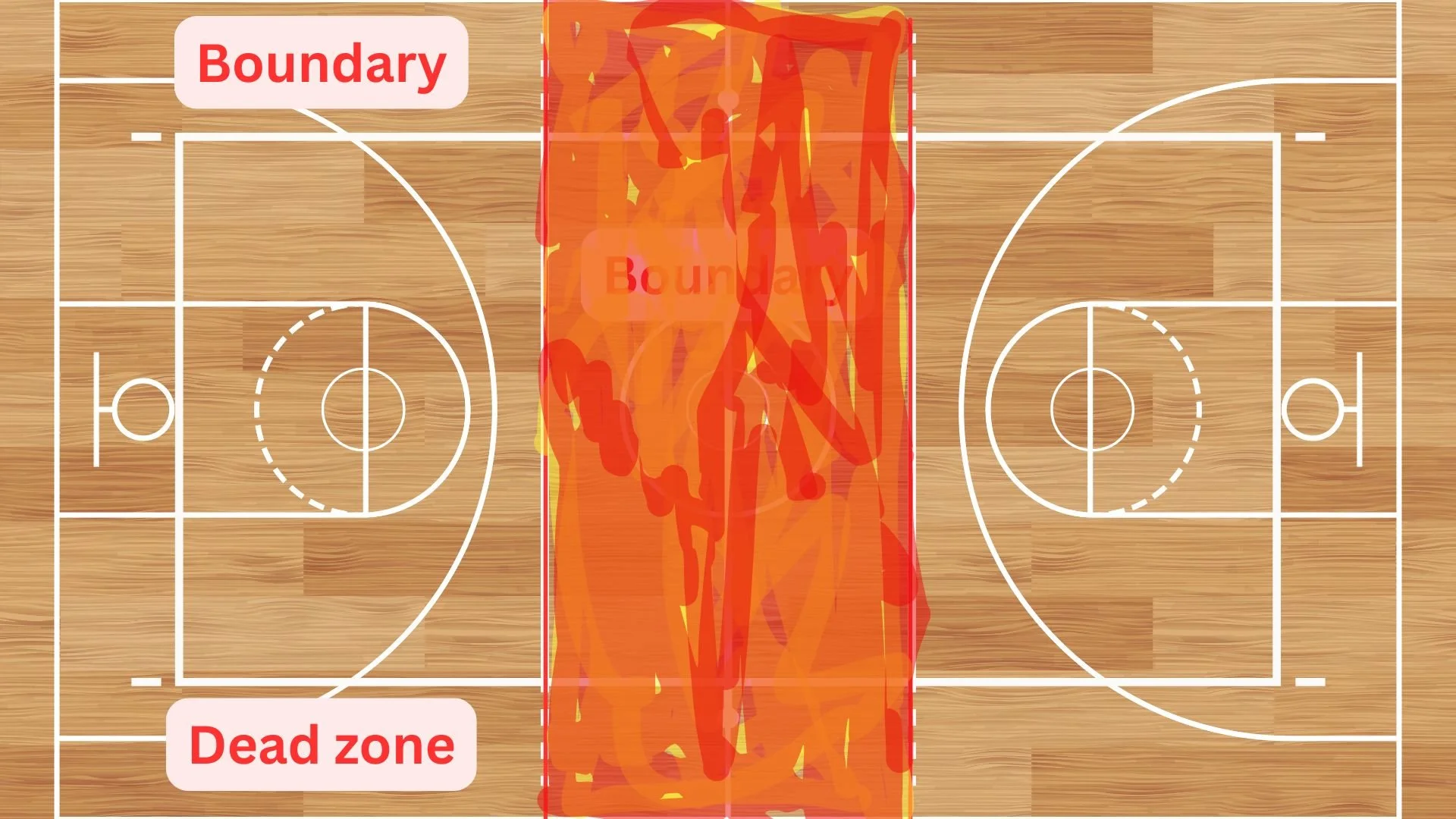

· For the fourth round, we eliminate the middle third of the playing area. There is essentially a “dead space” right in the middle of the playing area that players are not allowed to cross into, even if a ball rolls into the center. We use the volleyball court lines to mark the middle restricted area, and we extend them all the way past the volleyball court.

· For the fifth round, we essentially make the entirety of the volleyball court a dead space. This creates a unique playing arrangement that resembles a "U," as players are allowed to stand far back in the center but get much closer to the half-court line on the sides.

· In the sixth round, we remove the half-court line as a boundary, allowing players to run anywhere they want. Each team should start with half the dodgeballs. Players with a ball are not allowed to "tag" someone out; the ball must be thrown.

· For the seventh round, remind the students of this rule: “If a seated player catches a dodgeball, they are allowed to stand up and play again.” Almost always, the students have not been tossing a ball to one of their teammates to rescue them; they just assumed that they were trying to catch only the opponents' throws. Now that they understand they can "rescue" teammates, this will dramatically change how a player plays the game, especially when there are no more boundaries. Some will opt not to throw a ball at an opponent but to act more like a "medic," rescuing teammates who are sitting down.

· Once the gym time is over, bring the students together for the debriefing. Discuss which variations were the most fun and which were not so fun. The thing is, not everyone's favorite will be the same, and that's great! That reminds us that sport must be fun, but not every sport is fun for everyone.

· Finally, we will remind the students that once they have a final prototype of their new sport, they should experiment with the boundaries. They witnessed firsthand how changing the playing area dramatically impacted the game.